Entrance to Khakum Wood. (Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.)

Christopher Wigren, Deputy Director

Parks, campuses, estates, cemeteries, subdivisions, and much more—survey teams fanned out to record historic landscapes created by the Olmsted firm last week. In all, the teams visited about 100 sites in every corner of the state as part of the Olmsted in Connecticut project.

The project, a joint effort by Preservation Connecticut, the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office, and consultant firm Red Bridge Group, aims to document the heritage of Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and the pioneering landscape architecture firm he founded (1857-1979) in the state. Work will include inventory forms for approximately 150 sites plus a statewide context report outlining Frederick Law Olmsted’s background in Connecticut and his and his firm’s landscape work in the state.

As Preservation Connecticut’s coordinator for the Olmsted project, I was able to tag along with consultants during the week. Here are a few highlights:

- Walnut Hill Park in New Britain (1870), an early work by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, its sweeping lawns, clusters of informal mature shade trees, and hilltop views over the city epitomize Olmsted’s natural looking but carefully designed park designs, conceived to provide respite from city life for all segments of society.

- The burial plot of Seymour Cunningham in Litchfield, designed in 1911: unlike conventional grave plots, the Cunningham burial site sits atop a boulder overlooking the rest of the cemetery and surrounded by trees and ferns in a tranquil glade.

- Khakum Wood, in Greenwich: Olmsted Brothers laid out this subdivision in 1926, carving out lots, sketching roads, and making recommendations for siting houses and driveways. They also created landscape plans for some of the individual houses; one sits amid rock outcroppings and looks out over a rhododendron-planted hillside toward a pond.

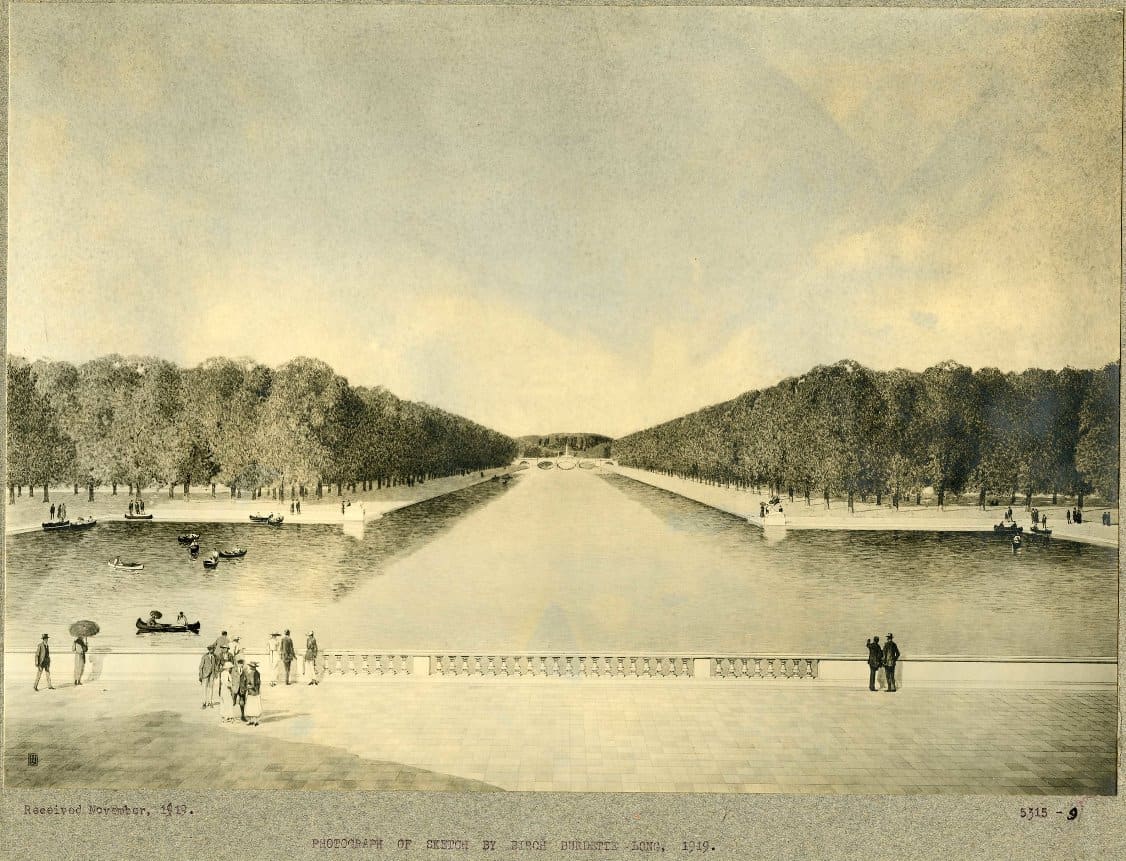

- A mysterious mile-long canal in New Haven’s West River Memorial Park (1919), turned out to be a fragment of a never-completed plan for an imposing World War I memorial whose formal design would have shown a different side of the firm’s work.

The Seymour Cunningham burial plot overlooks the East Cemetery in Litchfield.

This sketch for the never-completed West River Memorial Park in New Haven shows a formal canal leading to a memorial obelisk perfectly centered on West Rock. (Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.)

Consultant Lucy Lawliss talks with youth from Groundwork Bridgeport about her career as a landscape architect for the National Park Service.

In addition to the work of historical documentation, the consultants took time for some public outreach along with SHPO and PCT staff. In Bridgeport, we met in Seaside Park to talk about careers in landscape and historic preservation with youth and staff from Groundwork Bridgeport, which works revitalize parks and open spaces. And in Hartford, the team

answered questions and listened to hopes and concerns from members of the Friends of Keney Park, the Ebony Horsewomen, and the Garden Club of Hartford.

The project should be done in time for the 200th anniversary of Olmsted’s birth next April. Follow Preservation Connecticut for periodic updates.